ARE ELECTRIC SCOOTER SAFE ?

A LOOK AT THE AVAILABLE DATA ON THE SAFETY OF ELECTRIC SCOOTERS

Since the tragic death of YouTuber Emily Hartridge, when she collided with a lorry while riding an electric scooter in London in July 2019, there has been an increase in interest in the safety of electric scooters (e-scooters) both by the public and the authorities. Unfortunately, as is often the case in such circumstances, there was something of a knee-jerk reaction by the British government and, in turn, London police forces (I have made FOI requests to both the Met Police and City of London Police to understand the extent of their "crackdown"). My immediate thoughts on the announced crackdown on e-scooters were that it was done before a coroner had reviewed Ms Hartridge's accident and that, when cyclists die in road accidents, the inclination is not to blame the bicycle (but rather the larger vehicle).

There seemed to be a presumption that Ms Hartridge was somehow at fault - or that scooters are inherently dangerous - because she was riding a vehicle that is currently illegal to ride on public roads in the UK. However, if someone were riding an illegal fixed-wheel bike (with no brake) and was hit and killed by a lorry, would the presumption be that the cyclist was to blame? There were no headlines relating to a crackdown on fixed-wheel bikes after Kim Briggs was killed by a fixed-wheel cyclist in London.

Of course, I love e-scooters and we sell both the Ninebot Max and the Iconbit Tracer, so my instinct is to defend them but let us look at the relevant data to see what it says (or does not say). I will try to consider the safety of e-scooters impartially, using the available (but admittedly limited) data at the time of writing (August 2019). l will also see if it is possible - or even useful - to compare the data with that for cycling, note the limitations of the data and comparison, consider why injuries occur (and not just how) and how riding electric scooters can be done more safely. It is perhaps surprising that neither the government nor Transport for London has done this.

The Popular M365 and ES2 Electric Scooters

Perhaps the first thing to note is that there is a large variable that most analyses of e-scooter injuries fail to address, and which lessens the robustness of the data, especially when it is compared with bicycles. That variable is the makeup (personality) of e-scooter riders. Electric scooters are new and fun to ride. Although the data on their safety comes from countries where they are legal to ride, the people who ride them seem to be seeking fun as well as transportation and are not apparently taking safety into consideration: a fact borne out by the worrying number of helmetless riders. For instance, the CDC (Center for Disease Control) report, which is one of only two relevant reports, looked at riders hiring scooters in Austin, Texas, and found that only one of the 190 injured riders was wearing a helmet. It is thought that this reflects the low number of e-scooter riders who wear helmets generally. By contrast, half of cyclists in Texas wear helmets so it is fair to say that cyclists seem to be more concerned with safety. Thus, when comparing e-scooters with bicycles, it is important to remember that any discrepancy cannot be put down to the e-scooters only but that the rider must be taken into account.

It is also important to represent data truthfully and accurately. News outlets (or any website) can make misleading claims. For instance, this Business Insider article led with the headline "Electric scooters were to blame for at least 1,500 injuries and deaths in the US last year". However, the author was referencing this article by Consumer Reports (the equivalent of Which? in the UK), which stated only that there had been over 1,500 confirmed injuries plus four confirmed fatalities; so to write a headline in which "injuries and deaths" are grouped together when the deaths comprise only 0.26% of the statistics smacks of sensationalism and, to be fair, poor journalism.

Even representing the correct data in a certain way can make it sound worse. For instance, the Austin report, which analysed nearly one million scooter rides, states that 20 in 100,000 scooter rides ends in injury. That is the same as saying 1 in 5,000 scooter rides involves an injury, which somehow sounds less scary. So why did the authors choose the seemingly arbitrary denominator of 100,000 when it is arguably more useful to know how many rides are undertaken per injury? But let us look at this report in more detail.

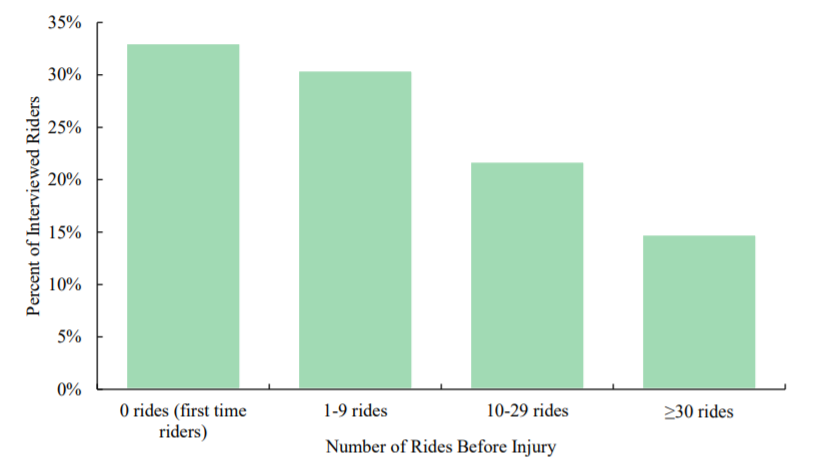

One of the most interesting findings of the Austin report is that 35% of the injuries occurred on the very first ride so, assuming you complete your first ride uninjured, the figure would drop to 1 injury in every 7,610 rides; meaning that if you rode your scooter twice-a-day for ten years you could expect to have one injury. However, perhaps the most striking aspect of the report is that, taking the data at face-value, if you wear a helmet, this figure drops down to 1 injury in 936,110 rides. This is because, as already stated, only one of those injured was wearing a helmet. So the report suggests that wearing a helmet while riding an e-scooter (and you should) means that you could ride twice-a-day for over 1200 years and expect to suffer one injury. This, of course, highlights the problem with this particular data set: a helmet in itself cannot account for a near 200-fold decrease in the likelihood of injury (when the injury can occur anywhere in the body). The most obvious explanation is that those who wear helmets are more careful generally and thus less likely to suffer injury.

Number of Rides Before Injury in Austin

The second report that tried to compare the number of injuries with the number of trips was carried out over 120 days in Portland, Oregon. Although a slightly longer period than that of the Austin report, it covered fewer rides - 700,369 in this case. The authors reported a total of 176 injuries (like the Austin report, most injuries - 83% - did not involve another vehicle). This equates to 1 injury in every 4,000 trips, but the data did not take into account how many of the injured riders were riding their own scooters, so it is likely to be a higher number. Unfortunately, it is not known how many were wearing helmets (because state law demands riders wear them), though only six were known to be riding a helmet while 23 were known not to be wearing a helmet (despite it being illegal).

There were no deaths reported in either the Austin or Portland reports (which covered over 1.6 million trips). According to the National Association of City Transportation Officials, there were 38.5 million e-scooter trips in the US in 2018, while there were four e-scooter fatalities reported. These were: Esteban Galindo, 26, in Chula Vista, California; Jenasia Summers, 21, in Cleveland, Ohio; Carlos Sanchez-Martin, 20, in Washington DC; and Jacoby Stoneking, 24, in Dallas, Texas. None of these riders were wearing helmets. There has been more deaths in 2019 but there is no data on the number of rides taken. Using the 2018 data, this means that there is approximately one death for every 9.6 million rides. It is perhaps worth noting that Ms Summers' death in Cleveland was the result of a drunken driver, who was imprisoned for causing her death (though it has no bearing on the statistics as we are not comparing who was at fault).

According to the UK Government, each person in England made an average of 17 bicycle rides a year from 2015 to 2018. There are 55.6 million people in England, so that equates to 945 million cycle rides each year. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents states that there were approximately 18,500 cycling injuries and 92 deaths in 2016 (figures have not been released for 2017/18 but are expected to be similar). That means there is about one injury per 51,100 cycle rides and one death per 10 million cycle rides. This indicates a greater likelihood of injury (by as much as a factor of 10) riding an electric scooter when compared with riding a bicycle but not much difference (a 5% increase) in the risk of death riding an electric scooter when compared with riding a bicycle. The discrepancy between the increased risk of injury against fatality is somewhat anomalous: it suggests that, if you are injured while riding an e-scooter, you are less likely to die despite the fact that you are less likely to be wearing a helmet. One explanation for this may be the greater ability for an e-scooter rider to jump off their e-scooter - to relative safety - when they are involved in a collision with a motor vehicle; while a cyclist does not have the same opportunity of "escape". This theory would need to be tested with computer simulations.

Despite the fact that you are apparently no more likely to die riding an e-scooter, there is still the question of why riding an e-scooter engenders a greater risk of non-fatal injury. The first clue as to why this might be has already been alluded to. It is the fact that, according to the Austin report, most (65%) injuries occurred within the first ten rides. This suggests that riders need time to get used to riding e-scooters before they can be considered competent enough to ride them as safely as a cyclist. The second possible explanation may also be revealed by the Austin report. That is the fact that nearly half (48%) of the reported injuries were head injuries. This suggests that, as none were wearing a helmet, that wearing a helmet would immediately lessen the number of injuries by about half (it was a statistical anomaly that, according to the report, riding an e-scooter with a helmet reduced the risk of injury to one every 1200 years).

The third possible explanation is also found within the Austin data: a third (29%) of those injured admitted to having drunk alcohol in the preceding 12 hours. The figure for injuries where alcohol was a factor for cyclists was put at 11% in 2006 (and must surely be lower in our Frappuccino-drinking times). The greater number of alcohol-induced accidents with e-scooters is probably due to the availability of dockless e-scooters in city-centres at night. The fourth possible explanation for the increased risk in e-scooter riding is a mix of data interpretation and anecdotal evidence: 83% of the e-scooter accidents did not involve another vehicle (or pedestrian), meaning that riders are literally falling off their hired e-scooters. Some admitted hitting the curb but there was no real explanation for the majority of these. I would postulate - from personal experience and anecdotal evidence - that the smaller wheels of an e-scooter mean that riders are more likely to come off when they hit a pothole or a similar obstruction.

One swallow does not a summer make. As tragic as Ms Hartridge's death was, it does not tell us anything about the relative safety of e-scooters. It only tells us that it is possible to be killed while riding an electric scooter. It is also possible to die while walking in London (58 pedestrians were killed in the city in 2018) and no-one is suggesting confiscating footwear. There is no data on how many e-scooter rides are taken each day or how many accidents resulted from riding e-scooters in London, England or the UK as a whole.

When comparing the statistics on e-scooting in the United States with the statistics on cycling in England, as far as fatalities are concerned, e-scooting is found to be no more dangerous than cycling; and this is despite the fact that e-scooter riders are much less likely to wear helmets. There is, however, more likelihood of non-fatal injury. Thus, by the most accepted definition "dangerous", it is fair to say that e-scooters are currently more dangerous than bicycles. There are several limitations on this comparison though:

Firstly, it does not take into account the length of the trips. Secondly, it does not take into account the location of the accidents: the e-scooter figures come from two urban settings whereas the cycling data comes from both urban and non-urban settings. Thirdly, the comparison is between hired e-scooter and (mostly) owned bikes, meaning a contrast in familiarity may be distorting the figures. Fourthly, the comparison also fails to take into account the comparative safety-consciousness of American e-scooter riders and British cyclists (though British cyclists are more than 10-times more likely to wear helmets than the former).

As noted, there are several possible explanations for the increased risk of injury when riding an e-scooter, with the most evidentially supported explanations being that riders are simply not experienced enough to ride safely and riders are not wearing helmets.

When there is no supporting data, you cannot claim that e-scooters are "dangerous" (a relative term anyway) simply because one person has died while riding an e-scooter in the UK. I am reminded of my mother's claim that an aunt smoked all her life and lived into her 90s, as if a sample of one disproves all the peer-reviewed reports showing that cigarettes are life-shortening. I believe that (as with cycling) safety education and perhaps a law enforcing the wearing of helmets would be a better solution rather than the confiscation of e-scooters (surely the police have better things to do?). Added to this, ensuring cycle lanes without potholes are available for riders would help prevent accidents. It is obvious that something needs to be done about the traffic and air pollution in British cities, especially London, and e-scooters have been shown to lessen the number of car journeys taken and, consequently, promote cleaner air.